Author Interview with Jocelyn Jane Cox

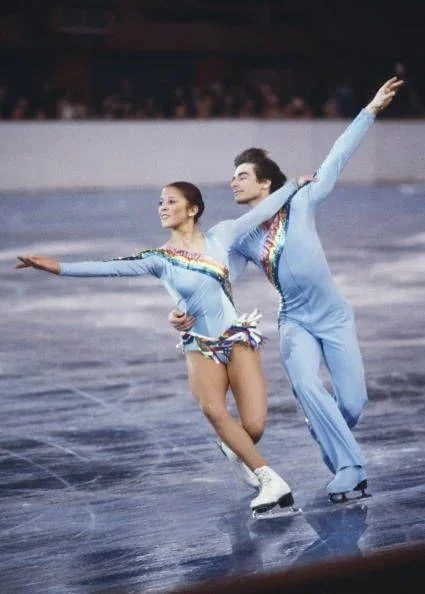

When eight-year-old Jocelyn Jane Cox sat down in her living room to watch the 1980 Winter Olympics, she could not have imagined training as a competitive pair figure skater for the next eleven years or going on to coach the sport for another twenty.

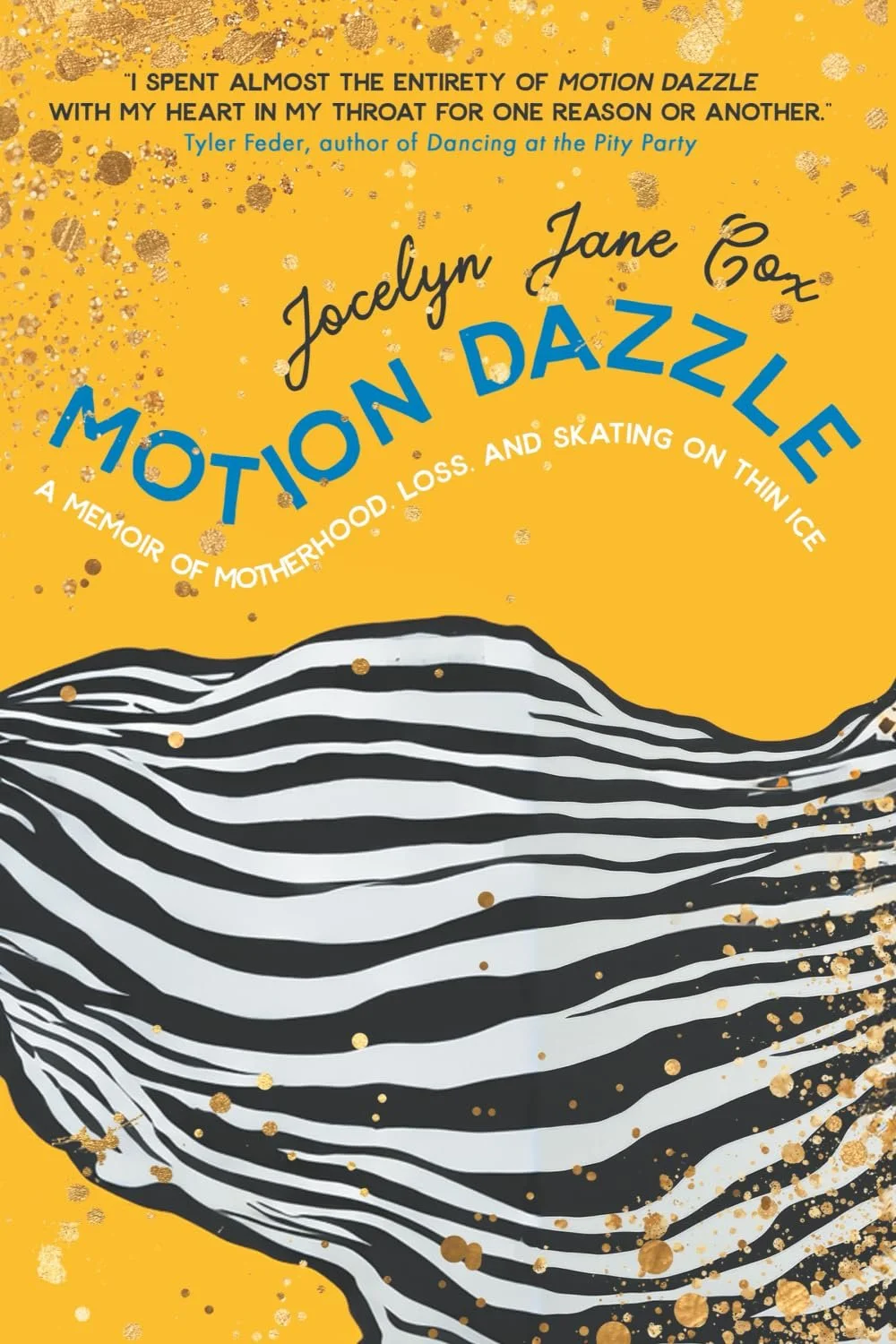

But skating was just one world Cox would inhabit, just one identity that would shape her life profoundly. In Motion Dazzle: A Memoir of Motherhood, Loss, and Skating on Thin Ice (Vine Leaves Press, 2025), Cox illuminates and examines her many worlds and identities and their evolution over decades, geographies, occupations, and relationships. Addressed to her son and centered on a single day—the day she is hosting his zebra-themed first birthday party—the story is also a tribute to the bond Cox shared with her mother, including the difficult final years of her mother’s life.

Cox spoke with Under Review fiction editor Carlee Tressel about her memoir, as well as “Hold Your Line” [LINK] and “Doll Hospital,” [LINK] two flash essays Cox contributed to Issue 13.

Jocelyn Jane Cox

In her own words, Jocelyn Jane Cox is a mother, daughter, caregiver, writing coach, eyeglass collector, and zebra fan. She competed in the U.S. Figure Skating Championships four times and coached the sport for over two decades. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Sarah Lawrence College. Her work has been widely published in national outlets like The New York Times, Slate, and The Boston Globe, and literary magazines like The Offing, Cleaver, and the Colorado Review. Her fiction and nonfiction have been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She lives with her son and husband in the Hudson Valley of New York.

Carlee Tressel is the fiction editor for the Under Review. She has selected, refined, and published short stories for eight issues (Issue 6/ Summer 2022 through the current issue, 13/Winter 2026). Prior to joining the team, her essay, “Pinup Girls,” was chosen for inclusion in Issue 1. Don’t make Carlee choose which part of her work for tUR she likes more: working with authors on their stories or having conversations like this one.

This interview was conducted via Zoom in December 2025. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Carlee Tressel: What I appreciated most about Motion Dazzle is its many threads—or “stripes,” as I’ve heard you explain it—which include your relationship with your mother, being her caretaker, your own relationship with motherhood, your experience as a figure and pair skater, and your career coaching figure skating. How did you come to write about these personally significant topics in this particular way?

Jocelyn Jane Cox: I knew I was dealing with a lot of elements that were seemingly disparate. But I do think we all “contain multitudes.” I understand the conventional concept of deciding on a theme for your memoir and sticking to this one theme. However, I think we all have so much inside of us, and we all have various experiences that might be very different from one another. The other thing the book contains is zebras! So I knew that I was dealing with a lot of different types of threads and I was determined to do the work to figure out how to put together all of these aspects of my life in a way that could possibly make sense to a reader. [Laughs]

That process included many, many, many revisions. I stopped counting at fourteen. [Laughs] There were many revisions. I had twenty beta readers. I understood that it was a tall task, and I was up for it.

CT: Tell us about the “striped” format. I love that descriptor, clearly a nod to the zebras in the story.

JJC: I love reading fragmented work. I just do. Of course I can also enjoy a standard, chronological and flowing memoir or novel, as well. But I do believe that the brain works in segments, and memory works in segments. And when we think back on our lives, we’re not thinking in some chronological, organized flow. I think we have these discrete memories and moments. It was my goal to capture those and trust that they were all going to flow together but that I didn’t have to necessarily create all the connective tissue.

I also very early on latched onto the metaphor of zebras. The book follows the day of my son’s first birthday party, and I randomly—extremely randomly—chose zebras as the theme. I had not been a fan of zebras before this time. So zebras are striped across the cover of the book and are a big part of the present day, or the most-present storyline. That metaphor of stripes gave me a lot to work with. So when I’m thinking of a segmented memoir, I am thinking of those as stripes.

My publisher was very cool to format this, at my request, with white space between every paragraph so I could have the visual of stripes, too. This was more of an internet formatting, where you don’t indent and you leave a space between paragraphs. This created a somewhat staccato and punctuated effect to the eye, I thought. I didn’t know if the publisher would do it. They said, We’ve never done it before, but because you have a reason and it connects to your story, we’ll do it.

CT: How was working with your publisher, Vine Leaves Press, overall?

JJC: Amazing. It has been so great. The beauty of working with a small press is there is a lot more creative freedom for both the press and the author. For example, the unique typeset and formatting. And getting a beautiful and respectful edit. I was very concerned when I went out on submission, and I did start with agents, but I was worried all along that my quirky book about figure skating, zebras, dementia, caregiving, and new motherhood was going to be tamed a little bit. I wanted it to be a wild animal. I leaned into the weird when I was composing it. I didn’t want to change that too much. The edit I received was so respectful of that. My editor, Melanie Faith, was absolutely accepting of all the weird stuff I did, and made a few excellent suggestions to make the book even better. I received a great copyedit, too, which I very much needed. It’s just been a really cool process.

CT: It sounds like you feel like the book remained yours. It wasn’t that you said farewell to it, passed it off, and it grew up to become something else.

JJC: Absolutely not. It was fully honored. When I first wrote the book, I had no chapters. I just thought I would segment this thing, and it would just roll, and I would have no chapters. That was the biggest thing the editor convinced me of: you have to have chapters, otherwise it will be really tricky for an audiobook and it will be really tricky for an e-book. That was quite convincing to me. By the time she made that suggestion, I was starting to think maybe I needed that, too. I had enough literary devices and unconventionality going on that, yes, I could impose some chapters on this beast. [JJC and CT laugh] I am so glad I did. There was some tinkering to be done when I “chapterized” it, but it actually made a lot of sense and I am so glad I did it. I do have an audiobook and I do have an e-book. And as a reading experience, I think it’s working better, as well.

CT: When in your process of writing and revising did you decide to center the story on this one day?

JJC: Day one. I just always loved this frame. My background is in fiction. I studied fiction in graduate school, and I attempted a novel, but I mostly wrote short stories. So I think writing the story of a day was creating a smaller scope for myself: I’m just going to tell the story of a day, and then I am going to go back in time, no big deal. [Laughs] I think I was trying to take off some of the pressure. I’ll do this contained little thing—a day—and just see where it goes.

I wasn’t conscious of this at the time, but it’s very much the structure of Mrs. Dalloway: A woman is preparing for a party and we get all of her inner thoughts and jump around in time in the backstory. Completely different content and context, but a similar setup. I read the novel as a young person and haven’t read it in a long time, but I think it might have been somewhere in my subconscious. That was a fun thing to discover.

CT: Was there a time when you couldn’t or didn’t want to write about your experiences with pair and figure skating? Or, to put it differently, did you know when it was time to start writing about that?

JJC: When I started writing this book, it was January 1 of 2021. I was about one year out from my figure skating coaching career. I coached for over 20 years, full-time. My last day of coaching skating was the day before the pandemic shutdown. So by that point I’d been home for almost a year, and I had experienced some distancing from the sport. When you become a coach in your sport, that means you’ve been living inside your sport for many decades, since you were a little kid. Since I was eight years old, I have been inside this world of figure skating, what I’ll call the snowglobe of figure skating.

CT: Love it.

JJC: I did write about skating many, many times while I was still coaching, but I was taking a more humorous, lighthearted approach. I had a blog for many years called Current Skate of Mind. [CT and JJC laugh] It was mostly humor and maybe some interesting coaching tidbits. It’s not that I was repressing the more difficult or darker sides of the sport, but I just don’t think I was ready to write more openly about that. By the time I did start writing about the more difficult parts of the sport for me, it was almost like I was an ex-pat. People move out of their country and then they can see their country more clearly. I felt like I was a bit of a skating ex-pat. I hadn’t fully decided that I wasn’t going back to coach skating, but I had really distanced my brain and my heart from it in a way that I hadn’t for forty years. So I think I was able to see the ways that it had maybe been difficult or harmful for me, but also be able to express it and find the words for it.

And this process of writing the book was definitely an experience of healing and forgiveness. Healing from some of the damage that I still experience from the sport, some of the disappointment and maybe resentment toward the people in my life who I was really hitched up with (my mother and my brother). That was therapeutic. People resist that word like it’s not legitimate to call writing or memoir writing a therapeutic experience, but I absolutely think that it is and can be. I fully own that and will fly that flag. Is it only therapy? No. Is it the only form of therapy someone should get? No. But it’s in there. It can be very helpful to work through these issues and ideas and recontextualize it on the page.

CT: Yes. Well said. If we can go here, something that struck me while reading Motion Dazzle and your two flash pieces that appear here in Issue 13 is the fear you felt as a young skater, how often fear was named in the narrative. How do you get there as a writer, to embody those very physical moments and scenes? Is it any different from how you get there when writing about other things that don’t have to do with the actual safety of your body?

JJC: I think it is a process. When I first started writing it it was very surface level and I challenged myself to go deeper and deeper into the experience, and the sensory experience. [Pauses] Figure skating is dangerous. It just is. We see these very polished performances, but people are getting very hurt all the time. They could be stress fractures over time or they could be, you know, cracking your skull. Pair skating is arguably and undeniably the most dangerous part of the sport. Over the years with new accidents and injuries, especially head injuries, they kick up the helmet debate: Should figure skaters wear helmets, specifically the pair skaters? It always kind of gets shot down because it’s not as aesthetically pleasing. And also skaters don't necessarily want to wear it because it feels weird to have a helmet on. It adds a little weight and a slightly different visual experience for them, from inside the helmet.

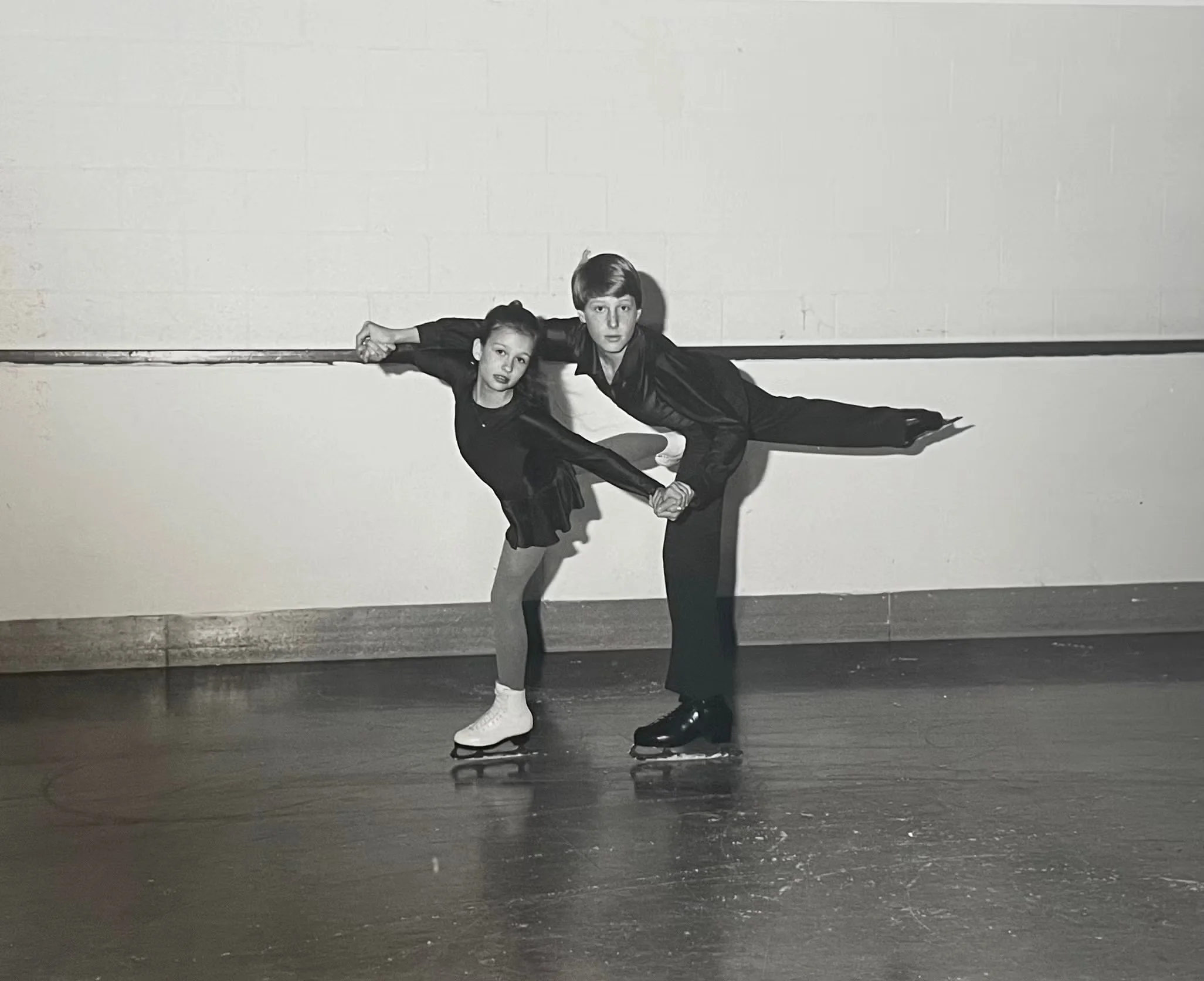

My own experience was that when I was younger, my brother had the task of lifting me and I had the task of being lifted, above his head, and we were careening across the ice. I was never a brave kid but here I was in the position of doing this. Really it was a steeling of myself as much as I possibly could. But in no way shape or form did I have the personality type for this particular kind of skating. I was exactly the wrong type of person to be doing it. And then I just grew too tall for it. To be a pair skating figure skater, you want to be more compact. It’s just physics. As I grew, I was not a compact person. I had long limbs. That increased the danger. So here I was already very fearful, and then I am doing the most dangerous part of the sport, and it’s arguably more dangerous for me because I don’t have enough size differential with my partner, who was my brother.

So as I write through these scenes and also as I go through the process of transferring all my VHS videos to digital, I am actually amazed that I did what I did, given how fearful I was and given how it was just a hope and a prayer. It’s kind of this concept now where we go up in a plane and we’re like, I don’t know how this machine works [laughs]. You just think, I hope it's ok. That’s how I went into literally every single element: I hope I’m ok. I lived in a state of fear, a general state of fear of every session, and fear of every little element we did in the session. It was kind of upsetting to reface, reacknowledge that, and revisit that…abject fear.

CT: No doubt. I appreciate you talking about it. It’s worth noting that fear of physical harm comes back into the story when you are preparing to give birth. You also reflect on how it was for your mother and for you to experience the deterioration of her health. What were you considering as you wrote about the limitations of the human body, in these related but distinct ways?

JJC: The human body is so resilient. And it’s also incredibly fragile. Getting hurt so often as a little kid made me afraid of pain and gave me a freakishly low pain threshold. I knew pain—from an optional, extracurricular activity—and I knew I didn’t want more of it. So, yes, childbirth terrified me.

As far as my mother, she had a freakishly high pain tolerance and it was tested multiple times. I always wished I had some fraction of her physical strength or tolerance. While I think she weathered her illnesses and physical health challenges admirably, I was possibly more traumatized than she was, given my own fears and history. In the end, it was the loss of her cognitions that proved to be more than she could handle. That was extremely difficult for me to witness as well.

The author and her brother on the ice.

CT: Let’s talk about ambivalence. I’m drawn to sports literature that is honest about the ambivalence and resistance that can come along with sport, particularly in highly competitive or elite arenas. I found it fascinating that you’re very upfront in the story about how skating actually wasn’t your thing. It was your brother’s thing, and you got brought along with it. For you, it started with that moment—I loved this moment in the book—when you’re watching the Olympics and you’re so engrossed that the plate of spaghetti slides off your lap. What a marvelous image. What a powerful visual portent to the injuries you would sustain. When we started seeing your injuries on the page, I thought, “That’s the fallen spaghetti!”

JJC: I appreciate you picking up on that! With anything in life—I think we can apply this to jobs and other things, as well—it’s hard to leave something that you’re 50/50 about. It’s hard to leave a girlfriend or boyfriend if you’re like, Fifty percent of this is so good, and fifty percent of this is horrible! I think I was in that exact sweet spot. Fifty percent of it was amazing. I felt like a star. I was signing autographs as a kid. I was on the local news. I was getting out of school. It felt very fabulous and fancy and sparkly. My costumes. The music. OK, but I did not love getting injured. I did not like training. I did not like the cold. I did not like this constant repetitive nature of the sport where you just have to do the same thing over and over and over again until it’s better, literally for years.

So I think I just was in a real bind, not to mention that my family got so caught up in it. But I think that I am not alone. There are a lot of talented people that don’t end up loving it. They’re just really talented and everyone is praising them, and they’re like, I don’t really even love it. Or, you have these not so talented people whose bodies are maybe not ideal for the sport, who love it. And so they keep going.

People keep going for a lot of reasons. Another of those reasons is the literal sunk cost, from a financial perspective, and all of the years of sacrifice that families put into their sports. Family dynamics can become so complex that no one can really figure out how to extract themselves or escape from the sport. And I think they end up being a little bit a prisoner of the sport.

So I think there can be so many reasons for people to stay with the sport that have nothing to do with loving it, unfortunately. And yes, I am also very drawn to those stories because it’s a complicated web that we weave as we move forward in a sport every single year.

CT: Your mother is very much at the center of Motion Dazzle, in every stripe. You say at one point that she's not your typical “figure skating mom.” I appreciated that we get a nuanced look at her story, that her reasons for ultimately supporting your brother’s and your skating career were complicated and rooted in her own things. Yet they break the over-invested parent trope that we see a lot of the time in youth sports stories.

JJC: I really respect my mom for the energy that she brought to the sport and the way she did it, the way she was sort of in the background, the way she was letting us take the lead—I should say, let my brother take the lead and bring me along. Writing the book, I started to understand a little bit more about her motivations. As parents we are coming to our parenting journey—either rejecting what our parents did, or doing the opposite, or trying to replicate it, or some weird combination of all of those. She was making sure we were having these experiences she didn't. Not to mention it created quite a nice diversion for her as her life went on and her disappointments. I think it was a distraction. And that’s one of the themes of the book: I think sports can be a healthy distraction and I think they can be an unhealthy distraction as well. I can say that on an individual level and collectively as a society.

CT: YES.

JJC: I mean, the amount of money athletes—some athletes—can make, some coaches can make, some programs. It feels a little skewed how much focus we put on sports as fans and sometimes as parents and then sometimes as athletes ourselves. It can be a very worthwhile endeavor, and it can also be examined for how useful it actually is for our society. I think it’s very useful, but I think other things are maybe more useful too. [Laughs]

CT: I think it’s really interesting that you had a very mixed experience as an athlete doing skating, but then you coached for a long time. Perhaps you found more of a home in coaching than as an athlete? What accounts for that? How did you think about that as you were crafting the story?

JJC: You are correct. I think I enjoyed coaching more than I enjoyed skating. For one thing, it was less dangerous. [Laughs] I could be part of the sport from the side. Much lower risk. Not that coaches don’t sometimes get hit, by the way. I definitely wanted to make the sport fun for these kids, for it to be a positive experience. I led with laughter. I led with positivity. I led with compliments. I really tried to make it a positive and fun endeavor for every student I worked with. I can say now that doing it that way was a reaction to my experience.

It really was an opportunity to share something that I had done for so many years. Because skating was so difficult for me, I had to really learn how to do it. I was probably a mid-level talent. I had to actually absorb the technique. I couldn't just go out there and do it. I had to really learn the technique in order to get my particular body to do these things. Maybe because I had an interest in words and communication, I was able to convey that and have fun conveying it. Because I was simultaneously a writer, it was almost like, how can I explain this new thing in a new way with a different analogy or a different metaphor? It was a creative act. Figuring out how to get this kid with this set of variables to do this thing that is really difficult… I found that to be very creative, to figure out the psychology of it, the physics of it, the communication aspect of it.

CT: How has writing this memoir informed what you are working on now?

JJC: When I wrote the memoir, it got very long. I had to really shave it down. I think I got up to 92,000 words, and I ended up at 79,000. So everything that I cut, the only way that I felt I could cut it is if I made a scrap folder and said I will use this some way, somehow, somewhere. The two flash pieces in this issue are from things that I cut. I completely wrote them as their own discrete pieces, but they were moments that didn’t quite make it into the book.

CT: Have you satisfied your desire to write about skating?

JJC: While I was on submission with Motion Dazzle I started a new collection of essays that also deals with figure skating from a few different angles. Some of it is that work that I cut and then completely transformed. But I had to stop to focus all of my energy on promoting Motion Dazzle. Maybe I’ll come back to it later this year. I’m curious about what it’s going to look like after living in this book for so long and promoting it.

Talking about the book has been almost as fun as writing the book. In this conversation we’re having I’m learning more about the concepts and the same can be said about conversations I have around caregiving or dementia. I am continuing to learn. I’m going to come away from this conversation with new ways of thinking based on your excellent questions. I have a feeling some of these ideas will be folded into that collection of essays. Or I may pick up the collection of essays and no longer want to work on that, and I am open to that. If it’s no longer looking interesting to me, I’m cool with that.

Here’s 50/50 again—maybe this is a thing for me: Part of me never wants to write about figure skating again. I have other sides of myself and would maybe like to dig into those that have nothing to do with skating. And fifty percent of me is like, hey, this has been my life and it is interesting and people are interested in it. People can relate to it either as ex-skaters or ex-athletes of any kind, so I think there’s a lot more to be mined from the topic. I may or may not get sick of doing that mining.

CT: Now for what has become a regular question for the authors we interview: What sports-related story or poem do you hope someone will write so you can read it?

JJC: I am hungry for more personal stories from athletes who didn’t make it to the top. There are so many autobiographies and memoirs by people who made it all the way. We know that most of those memoirs were ghostwritten, and that’s OK. They didn’t go get an MFA and have this other writing plotline to their life like I did. So I forgive them for that. But I think it’s really fun to read real-life personal experiences from the field even if you did it on a recreational level and you didn’t go beyond high school or 8th grade. Whether or not we went to the Olympics, if we participated in the sport, it probably had some foundational impact on us, and I just hate to live in a world where the only memoirs we get to see are from the people who went to the top (and we know they didn’t write the book).

1980 Olympians Tai Babilonia and Randy Gardner, who inspired the Coxes

There are a couple of books I read recently that I would like to see more of: Keri Blakinger’s Corrections in Ink. She was a former figure skater who ended up, unfortunately, dealing drugs and going to prison for two years. Also: Gabe Montesanti’s Bracing for Impact. She had been a competitive swimmer, a very accomplished swimmer, who ended up not having a great experience and going on to be on a roller derby team in St. Louis. Those kinds of stories. I hadn’t heard their names before, but they have really valuable stories and I would like to put mine in that category. It’s the people who were not on the podium that I want to hear more from, either in personal writing, documentary, or screenwriting.

CT: Jocelyn, this conversation has been a true pleasure. Thank you for your time.

JJC: The book is one thing, and everything that comes around the book is this whole other thrill. I’m counting this conversation as a huge thrill—of being able to be understood in your weirdness, in your strange set of experiences. That is nothing short of thrilling.